By: Laurie Benson

Wednesday 13th April marked the launch of the Leverhulme Artist-in-Residence hosted by the Arts and Conflict Hub and Research Centre in International Relations, Department of War Studies, King’s College London. The residency features the artist Baptist Coelho who introduced his artistic practice at the event. An exhibition entitled ‘Traces of War’ will be held in November 2016 at the Inigo Rooms. Co-curator Cécile Bourne-Farrell stressed that the exhibition is an exploratory process to ‘recalibrate our vision’, not by transcending, but engaging with the everyday experiences of war and its locations. This article explores certain themes prompted by the upcoming exhibition and discussions, namely in terms of commemoration, the everyday, and the role of artists and art in conflict.

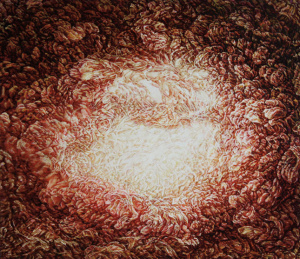

Baptist’s presentation took the audience on a journey from locations in India and Pakistan, to the living rooms of ex-British soldiers, and memorial sites in Brighton. Since 2006 he has engaged with the India/Pakistan conflict though a project entitled Siachen Glacier, exploring the extreme conditions experienced by soldiers on the border-located glacier battlefield. Notable pieces have included Ribbons I (2015) and “I long to see some colour…” (2009) an installation piece in which empty photo frames in a soldier’s rucksack suggest that what is not visible can still be present. From tales recounted to the artist embedded with the soldiers, the claustrophobic white landscapes of the glacier framed their reality day in, day out. So often saturated by the CNN-bannered news imagery or fluorescent aerial drone aesthetics, Baptist’s work and its realisation in the gallery space also stresses the banal palettes of conflict.

Working in mixed-media, from installation and photography to video, his practice draws on different textures, archival maps, booklets, interviews, and recently, gauge bandages. His aesthetic engagement prompts the viewer to consider the co-presence of different narratives; of what gets counted or not. Conflict involves human lives, bodily disposition, struggle, and the day-to-day. Focusing on objects juxtaposed in a cold display cabinet, for example, alludes to the proximity and distance of conflict and its display. How and through what frames is conflict viewed? What does an audience expect to see? What are the ethical and political implications of visibility and what is naturalised?

The role of the artist in conflict and politics has long been theorised, contested, and marketed. Art has been drawn upon to illustrate the horrors of war by academics, critics, and philosophers alike. Picasso’s Guernica is one of the most commonly cited examples. But perhaps what is also at stake is the practice, the doing. Artistic methods of researching and visualising intervene as much as they reveal; ways of working are potentially disruptive. They are also relational. Art is curated, exhibited, funded, viewed, and reviewed in contexts with audiences bringing their own frames of reference, expectations, and experiences in these processes of meaning-making. As Theodor Adorno reminds us, art works are both aesthetic and ‘social fact’.

Memories and traces of the past surface in the present, from war memorials, literature, film, and art, to personal stories passed through generations, and community claims left unrecognised in (re)articulations of the nation. How and what gets commemorated- its performance and symbolic cache- are political, intersecting the private and public. Public sites, for example museums and their collections, are not neutral but institutional spaces with bordering practices that intersect personal histories and official narrative. Baptist stresses engaging with the archive as a central part of his artistic research. The archive is active, not a relic of the past, but rather history in the present. An upcoming art project will look at the commemoration in a Brighton community for an Indian soldier fighting under the British in World War One. The recent controversies over the statue of Cecil Rhodes exemplifies the ongoing question of how a nation deals with its colonial past and what, and whom, are considered to belong. Judith Butler speaks of the ‘derealisation of loss’, of the politics and hierarchy of human experience, but Baptist’s work also suggests the possibility of thinking differently through and with art and its politics.

The exhibition supported by King’s Cultural Programming entitled ‘Traces of War’ will be held in the Indigo Rooms, from 26th October to December 2016.It is being curated by Professor Vivienne Jabri, Department of War Studies, and Cécile Bourne-Farrell. The exhibition will feature work by prominent artists, Jananne Al-Ani and Shaun Gladwell as well as pieces by Baptist as-yet exhibited in the UK. The residency, featuring the artist Baptist Coelho, is being supported by the Leverhulme Trust and the Delfina Foundation.

Laurie Benson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of War Studies

For more information about the artist please check:

http://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/departments/warstudies/people/baptist/index.aspx

Additional Information & Media: